For much of their existence, the idea of seeing 1. FC Union Berlin play against Bayern Munich seemed impossible to most fans. It was carved of purest fantasy, a feverish dream. For they had not just inhabited different countries for a long time, but different universes. By the early ‘90s, though the border had gone, one was gilded and glittering and feted; the other was largely ignored by the outside world – even by the city they represented – and faced a regular fight for their very existence.

But in 1993 an optimistic breeze had raised itself and started to blow across the Müggelsee to the Wuhlheide. Union were reigning champions – if only of the Oberliga; the third-and-a-half division – but they’d failed in their attempt to get a license for the 2.Bundesliga at the last attempt. It didn’t matter how they played, somehow. Stones always seemed to be cast in Union’s path. There were potholes in their lawn and weeds pushing up through the cracks in their concrete.

Union had shaken themselves down and dusted themselves off, and they would be buoyed by the impossible news.

It was like a gift – hidden in the garden with the over-boiled eggs and the bizarre stories of omnipotent, benevolent bunnies – the consequence of an arrangement thrashed out by Union’s boss, Pedro Brombacher, and his opposite number, Uli Hoeness, over two meetings in two hotels in two different parts of the city.

On Easter Sunday, just two days after beating Borussia Dortmund in the Bundesliga, the famous FC Bayern were to play against 1. FC Union Berlin at the Alte Försterei.

Okay, maybe a little of that shine had come off Bayern at that point. The season before they hadn’t qualified for Europe for the first time in 14 years. Jupp Heynckes had been fired. So had Sören Lerby.

It had been up to Erich Ribbeck and his assistants Hermann Gerland and Gerd Müller – seen in the matchday program flogging Opel Frontera Sports cars like spivs in tracksuits to anyone who’d pay attention – to claw them back to the top of the table.

Meanwhile Frank Pagelsdorf had built an Union side that were nine points clear at the top of the league with only six games to go. Maybe things really were turning their way this time.

They had five players in the list of the Oberliga’s top ten scorers led by the Zambian international winger Gibby “Cool it” Mbasela with 14 and, at the absolute pinnacle with 21, Jacek Mencel. Mencel was the first foreign player to play for the club, and he scored 78 times for Union, more than anyone before ever had.

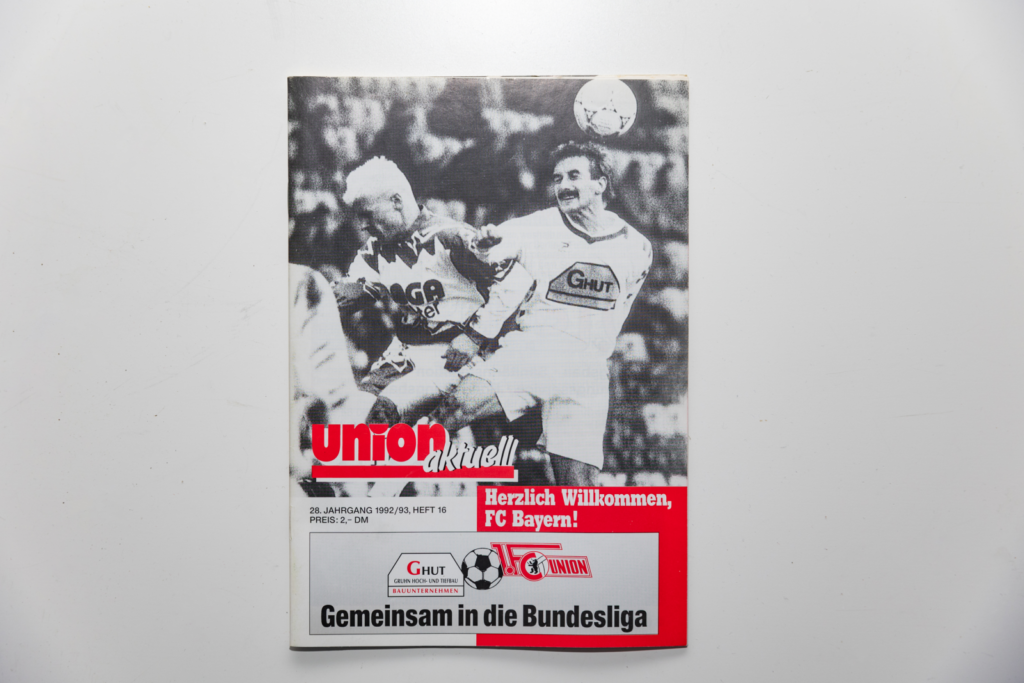

Türkspor had been thrashed 4-0 a week earlier. Marathon 5-0 the week before that. Andre Hofschneider was in the middle of a defence that had conceded ten goals fewer than Hertha’s amateurs, the next best in the league, and 47 fewer than Marathon, the worst. He’s there with his picture in the program, too, his expressive slitted eyes closed, heading a ball away from a pair of dispondent Marathon strikers, his long dark mullet swishing around behind him as he does so.

Hofi would soon leave, but he was drawn back to Union 15 years ago and is still there today, in charge of Union’s youth teams, as much a part of the stadium as the deep red bricks of the old scoreboard.

Bayern won the game 4-1 in the end. Bruno Labaddia and Roland Wohlfarth scored. Mehmet Scholl – the eternal talent, they call him, an allusion to an ethereal set of skills, somehow unfulfilled – scored two. Marko Rehmer scored the single goal for Union. The match report the following day doesn’t record how it went in.

It was the only time in his subsequent, injury plagued career, he’d ever score against them. He’d never be on a single side that beat Bayern Munich.

Union did win the league that year, and also the three team playoff round for that promotion spot, all by a single goal to nil. But it was all for nothing. A forged bank certificate from a still unknown employee saw them held back again, their place in the 2.Bundesliga taken this time by Tennis Borussia.

So it goes, so it goes. There was a certain crushing inevitablity to it.

Ultimately, Mencel too would leave Union, going across the city to the now hated TeBe. He justified the move later, saying that he had to do what was right for his family. The Unioner answered with a banner saying yes, of course he must. But what about his real family?

And despite the glee with which he scored, the manner in which he could beat opponents at will, or slow down time with the ball at his feet (hence the nickname, “cool it”) ultimately Mbasela would embody the fleeting nature of footballing glory, for he was about to dodge appalling destiny. On April 27th, just 13 days after Union hosted Bayern, 14 of his national team-mates were killed as their DC-5 plunged helplessly into the Atlantic. He was, it is said, supposed to be on that plane were he not playing in Germany.

Whatever the case, it was a tragic reminder that football can only enhance life, no goal is ever as important as it. He died at only 38 in Kitwe, the place of his birth.

And Bayern? Bayern wouldn’t win the league in 1993, missing out by a point to Werder Bremen. But they’d win it the year after that. And then a couple of years after that. And on and on they went, winning the German league title another 18 times.

But the joy that 15,000 people took at just facing them on an Easter Sunday in an unroofed, crumbling Alte Försterei in 1993 was palpable. For at the very least it meant recognition, like an invisible man being seen for the first time, it meant that they counted.

And, if just facing them seemed impossible enough, God only knew when 1. FC Union Berlin would get the chance to host the famous FC Bayern Munich in the league.

– Jacob Sweetman

With great thanks to Gerald Karpa, www.immerunioner.de and Nadia Saini